Why ageing is inevitable but decay is optional!

Why ageing is inevitable but decay is optional!

“Well I am getting old!”

This doesn’t need to be an excuse to live in pain, and to simply ‘put up with it’.

As a physiotherapist I seem to be increasingly hearing the ‘O’ word during consultations. What’s the O word? OLD. I purpose this article for the wider community and health professionals alike.

As well as giving me flashes of classic Die Hard dialogue, it reinforces my role as a physiotherapist in helping to educate, encourage, and implore people that age doesn’t need to be an unsurpassable barrier to living pain free, healthy, happy, and being able to do the physical things that they love to do.

Please do not let age be an excuse for injury, recovery, or your health status. Avoid attributing aches and pains to merely being the result of ageing and the ticking of the body clock.

Know that so much can be done to help control or eliminate your pain or injury irrespective of your age, in order to get you back to your physical best and enjoying that activities that you love to do.

Don’t succumb to attributing aches and pains to age! #physio #livelong #fperformbetter @pogophysio Share on X

Getting Older

Australia faces the challenge of a growing and ageing population. Australia’s population is expected to reach nearly 40 million by 2055 with nearly a quarter of that over the age of 65, according to the latest Inter-generational Report (1). This is an enormous number of people, who with a greater understanding of normal aging processes, and a knowledge of what can be done to help prolong health, can live healthier and happier lives.

Australia faces the challenge of a growing and ageing population #physio #health @apaphysio #peformbetter Share on XThe affects of ageing

We all age. It’s inevitable.

Muscle Tissue

With ageing there are numerous processes and changes that the body undergoes. Maximum muscle strength is reached by ages 25-30 years. Following which skeletal muscle cross-sectional area decreases (atrophy of type 1 and 2 muscle fibres) with age and with it the muscles ability to generate force (strength). This process can make activities that were once easy and effortless, difficult or simply unable to complete. This phenomenon is referred to as sarcopenia, and is the result of a reduction in number and size of muscle fibres and increased fat and connective tissue within the muscle (2).

Bone Health

From the age of 30 bone mineral density begins to slowly decrease. This decline accelerates in women after menopause. Reduced bone density (osteopenia or osteoporosis) increases risk of fracture and can lead to postural changes such as kyphosis (an exaggerated thoracic curvature or forward hunch). Alongside changes to bone mass, there are changes to the connective tissues with age. There are increased collagen fibre diameter, calcification within the tissues and reduced elastin in smooth muscle, which all reduce the ability of the tissues to stretch.

Joints

As people age, their joints are influenced by changes in connective tissue and cartilage. Articular cartilage creates a smooth, low friction surface between bony surfaces and disperses the mechanical loads of the joint (3). Initially articular cartilage loses proteoglycans, which results in it becoming weaker, less resilient to stress and thus predisposed to damage (4). The synovium releases increased inflammatory cytokines, which promotes greater breakdown of cartilage and thickening the synovium (3). There is an increased release of nitric oxide, which inhibits proteoglycan and collagen synthesis, promotes loss of cartilage cells and remodelling of the subchondral bone (4). This process leads to thinning of the cartilage and eventual exposure, stiffening and sclerosis of the underlying sub-chondral bone, forming the basis of osteoarthritis.

**Note: For an answer to the commonly asked question ‘Does Running Really Cause Knee Osteoarthritis ‘ Click HERE >>

General Performance

As well as all these physical effects of ageing, it also brings with it declines in our performance in a multitude of cognitive tasks (5). More specifically, processing speed declines early in the course of aging as well as working memory, reduction in reaction time and selective attention. Age also has well documented effects on the respiratory and cardiovascular systems, which have reduced capacity and links to numerous metabolic diseases.

All these changes are normal and will happen as we age. The importance then turns to how can we delay these changes, ultimately allowing clients to do the physical things they love to do in life.

Common Misconceptions

“I am too old to do that..” Are you really? Says who? I hear this so often. At times I feel like I am constantly working to show people that they are not too old and that they can do it. With age and experience, there is greater understanding of current capability, knowing what can or can’t be done. You can accept current capabilities as the best you can get and that your best days are behind you.

This doesn’t have to be the case, sure you might not be the glowing 20 year old athlete you once were, however you can decrease pain and improve overall function and health. Trying and failing physical activity, exercise or something as lifting the grand-kids, once, twice or even five times doesn’t mean you should never do it again. There is a very strong chance with the right advice, knowledge, exercises and progressions you can see improvement in both your function and your pain levels. There will exist a starting point from which with the right intervention you will experience improvement in your physical activity levels and function.

Ageing doesn’t need to prevent you from doing the physical things you love to do.

The Prevalence of Osteoarthritis

The prevalence of osteoarthritis (OA) increases with age. Statistics tell us that 30% to 50% of adults older than 65 years suffer from this condition. Radiographic (X-ray) changes of OA, such as the presence of osteophytes (bony changes) are very common. Radiographic surveys of multiple joints (hands, spine, hips, and knees) reveal OA in at least one joint in over 80% of older adults. However, it should be noted that there is poor correlation between radiological evidence of joint damage from OA and the experience of joint pain.

Up to 50 % of individuals with severe evidence of radiographic OA will have no joint pain, and many individuals with severe joint pain have normal imaging (6, 7). These studies and many more like it are optimistic, showing that although you may have osteoarthritis it doesn’t mean pain-free is no longer attainable and that continuing exercise will damage things more. It is actually quite the contrary, which we will see shortly.

Up to 50 % of individuals with severe evidence of radiographic OA will have no joint pain #physio #fact Share on X

Lower Back Pain

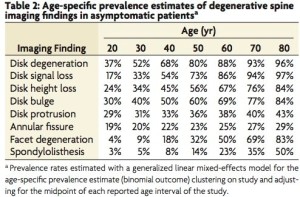

A similar story is evident when it comes to lower back pain. A recent study on asymptomatic (pain-free) individuals by Brinjikji and colleagues in 2015 has shown the prevalence on numerous radiological findings on imaging (see below). These findings are often attributed to be the cause of pain and symptoms, when they can be normal unrelated findings.

The above study findings raise the question- if we can see pain free, normally functioning people with these sorts of findings on x-rays, then why can’t symptomatic individuals potentially achieve the same with appropriate conservative management? The answer to this is complex and beyond today’s post. It links to a modern understanding of pain, in which pain is much more complex than just purely what is happening on a scan, at your back or knee.

**Note: For a previous post I wrote Pain Let’s Talk About It click HERE >>

The Role of Physical Activity

Exercise and physical activity are really the closest we get to a magic anti-ageing formula. Exercise slows numerous effects of aging, ultimately helping the thing you want and need to do for longer. Here are just some effects from aerobic and strength exercise:

- Maintain functional mobility and ability to complete daily tasks

- Maintain muscle bulk, strength, ROM and flexibility

- Maintain soft tissue extensibility

- Maintain mental alertness & positive self-image

- Reduced depression & anxiety

- Maintain bone density & strength

- Maintain cartilage health, protective of joint structure

- Induces peripheral adaptations to improve oxygen update be tissues

- Reduce blood pressure and improved cardiovascular fitness

- Reduce body fat and cholesterol levels

- Improve glucose tolerance, prevent Type II Diabetes

- Primary and secondary prevention of chronic diseases (cardiovascular disease, cancer, hypertension, obesity, depression, osteoporosis and diabetes)

- Physical activity combined with a socially integrated network and cognitive leisure activity can slow the rate of cognitive decline and aid prevention of dementia.

With all these great benefits it is clear that the myriad of roles exercise plays in both improving and maintaining our health. Starting exercise and experiencing these benefits is not always ‘straightforward’. We can all (irrespective of our age) experience barriers to exercise and physical activity; time, cost, motivation and often pain or injury.

So if “everything is worn away,” “you have arthritis,” or you’ve tried and failed to previously exercise, it doesn’t mean you should give up. I encourage you to not allow yourself to use your age as justification for avoiding physical activities or worse living unnecessarily in pain.

Yours in life-long optimal physical performance,

Lewis Craig (APAM)

Physiotherapist

References

(1) Hockey, J (2015). 2015 Intergenerational Report Australia in 2055. Commonwealth Government of Australia. ISBN: 978-1-925220-41-4

(2) Williams, G. N., Higgins, M. J., & Lewek, M. D. (2002). Aging skeletal muscle: physiologic changes and the effects of training. Physical Therapy, 82(1), 62-68.

(3) Goodman, C., & Fuller, K. (2009). Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist. St. Louis, Missouri: Saunders, Elsevier.

(4) Swales, C., & Athanasou, N. A. (2010). The pathobiology of osteoarthritis. Orthopaedics and Trauma, 24 (6), 399-404.

(5) Bherer, L., Erickson, K. I., & Liu-Ambrose, T. (2013). A review of the effects of physical activity and exercise on cognitive and brain functions in older adults. Journal of aging research, 2013.

(6) Loeser, R. F. (2010). Age-related changes in the musculoskeletal system and the development of osteoarthritis. Clinics in geriatric medicine, 26(3), 371-386.

(7) Creamer P, Hochberg MC. Why does osteoarthritis of the knee hurt–sometimes? Br J Rheumatol. 1997;36(7):726–8.

(8) Brinjikji, W., Luetmer, P. H., Comstock, B., Bresnahan, B. W., Chen, L. E., Deyo, R. A., … & Wald, J. T. (2015). Systematic literature review of imaging features of spinal degeneration in asymptomatic populations. American Journal of Neuroradiology, 36(4), 811-816.

(9) L. Fratiglioni, S. Paillard-Borg, and B. Winblad, “An active and socially integrated lifestyle in late life might protect against dementia,” The Lancet Neurology, vol. 3, no. 6, pp. 343–353, 2004