So you have ‘Shin Splints’? What to do next

Pain in the shin bone (tibia) has been reported to make up 12 to 18 per cent of all running injuries, with female runners experiencing shin pain more than male runners.

What are shin splints?

Technically ‘shin splints’ is not a diagnosis but rather an umbrella term that includes a variety of pathologies that can strike the region of the shin bone (tibia).

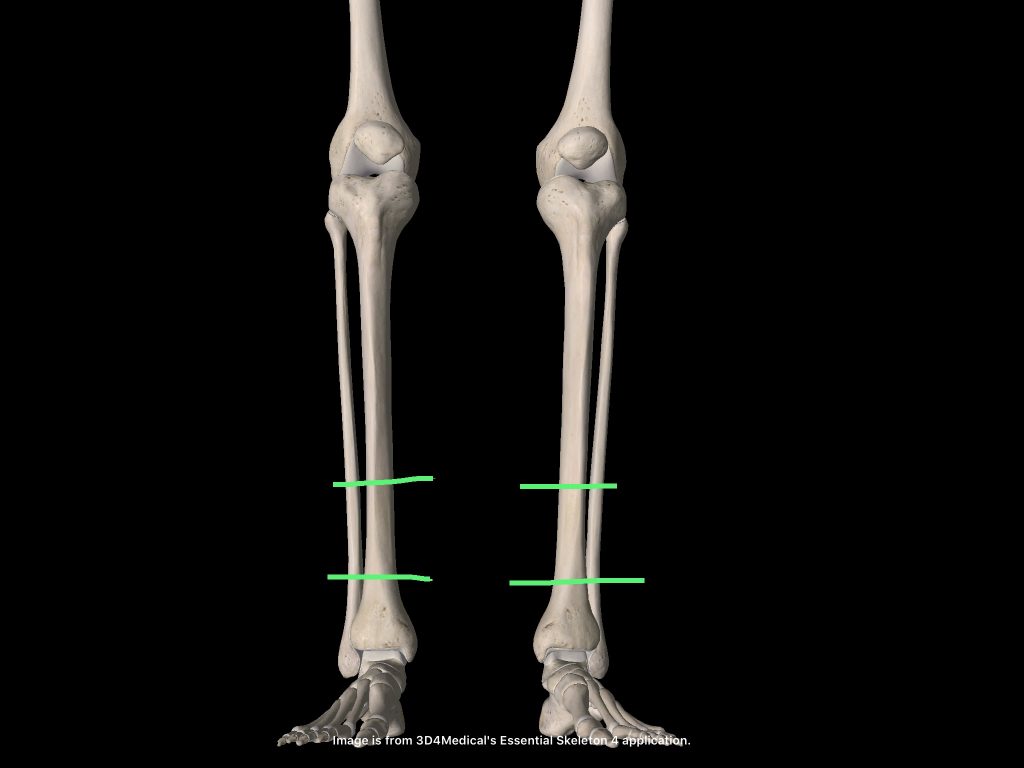

Shin splints characteristically affects the regions indicated above.

These pathologies can include problems with nearby tendons, exertional pains of the connective tissue near the shin, and a gamut of tibia-related pains. The medical term for shin splints is ‘medial tibial stress syndrome’ (MTSS). However, most people refer to this condition simply as ‘shin splints’. In practice, I tend to refer to MTSS as shin splints or ‘shin pain’ due to the familiarity of these terms among runners.

Many runners incorrectly believe that they have shin splints. #performbetter @pogophysio Share on XAuthentic shin splints develop in the bottom third of the shin bone. It is at this point that the shin bone has the smallest cross-sectional area, and so is the most vulnerable to repetitive loading and subsequent injury at this point.

The Shin Splint Continuum

Shin splints is a continuum condition, whereby the shin bone will progress from being normally loaded, to slightly overloaded, to very overloaded, to eventually incurring fracture. During the ‘overloading’ stages the bone becomes painful as the outside of the bone (the cortex) develops tiny microscopic fracture lines. At a cellular level, when pain is experienced the bone’s repair mechanisms are being outstripped by the bone being damaged and broken down.

The very end stage of shin splints is a tibial stress fracture. At this point the bone fails and fractures due to being repeatedly overloaded beyond its tolerance or ‘failure point’ through continued stress and loading associated with running.

The very end stage of shin splints is a tibial stress fracture. #performbetter @pogophysio Share on XA note on Compartment Syndrome

Many runners incorrectly believe that they have shin splints when they experience pain at the front and outside of their shin bone. Normally this is not shin splints but rather muscle and fascia tightness of the tibialis anterior muscle. The tibialis anterior muscles can be prone to becoming excessively tight when exercise is commenced (see image below).

Compartment syndrome of the tibialis anterior muscle and associated fascia accounts for most pain experienced to the front and outside of the shins.

Pain to the front and outside of the shin can result from reduced or restricted blood flow to the tibialis anterior muscle. Medically we term this pain ‘compartment syndrome’, and its cause is distinctly different to a true case of shin splints.

What Causes Shin Splints?

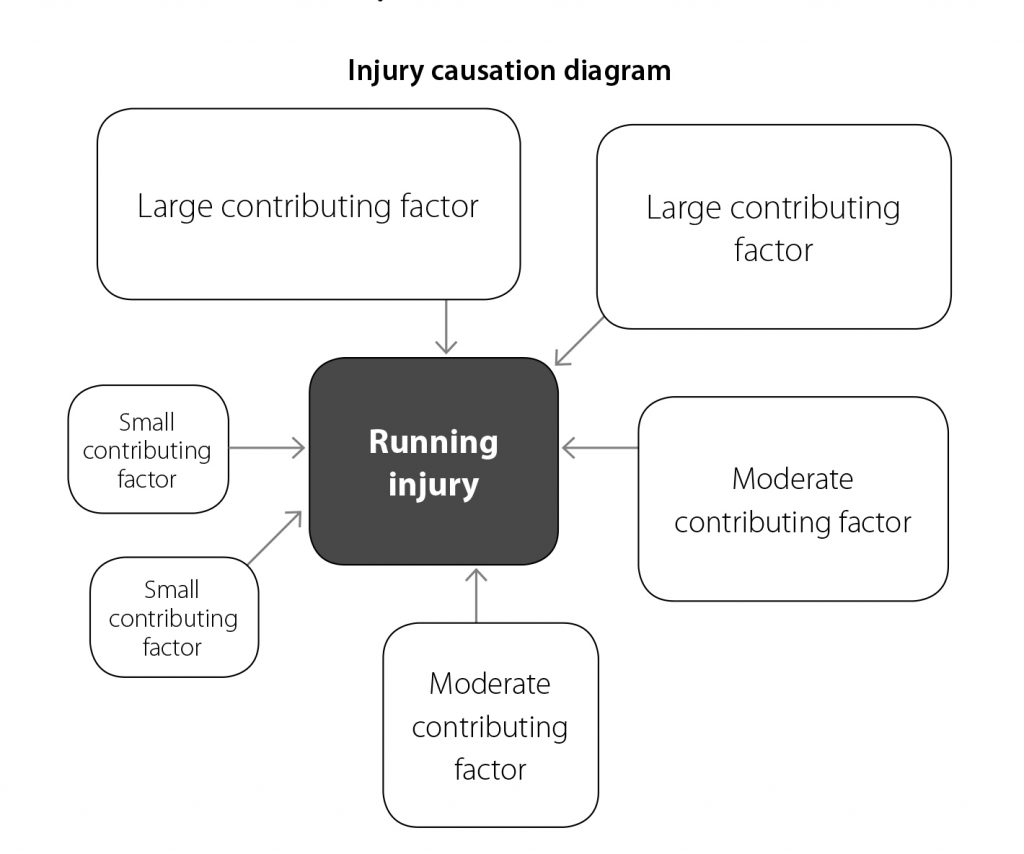

Like typically all running overuse injuries, the onset of shin splints is multi-factorial in nature. That is, there is a combination of factors that contributes to the onset of shin splints, as opposed to a single isolated factor. The image below demonstrates the multifactorial nature of shin splints.

Running Injury Causation. Source: You CAN Run Pain Free!page 63

There may be large contributory factors, and smaller factors that contribute to the onset of shin splints. The chief contributory factors can typically include:

- tight calf muscles

- weakness in the calf muscles

- training loads suddenly increased. I refer to such training load increases as training load ‘spikes’. Spikes can include the addition of extra sessions into a running program, the addition of hills, the addition of extra intensity running training sessions, or a failure to schedule sufficient rest between sessions. To learn more about common training errors click HERE>>

- addition of hills and hard surfaces to a training program

- inappropriate footwear (to learn how to select your next pair of running shoes click HERE>>)

- flat feet or dropped arches

- excess body weight (to learn more about our running ‘frame weight’ click HERE>>)

- poor running technique

From my clinical experience the top four contributory factors that coalesce together to create the onset of shin splints for many runners are:

- sudden spike in training load (normally volume and intensity)

- shoes that are no longer supportive (ie. the shoes are well and truly worn offering little protection from impact loading with each running stride)

- over-striding (click HERE>> to learn more)

- deficit in the required hip stability to run without injury (click HERE>> to read more)

How do you know if you have Shin Splints?

Signs to look for: pain in the bottom one third of the shin bone. The pain is felt on the inside border of the shin.

Initially, the shin will be sore to touch after running. As the shin bone continues to be overloaded, the pain usually progresses to being present at the start of a run.

Eventually if treatment and rest are not sought and adhered to, the shin bone will be sore before, during and after running. When a stress fracture occurs, the runner will have difficulty hopping on a single leg two to three times because the pain will be too great.

A good screening test that I give runners to determine the degree of sensitivity of their shins is the single leg hop test. If a runner cannot perform 6-12 single leg hops with confidence and without pain than they should typically not run that day (click HERE>> to view the single leg hop test).

How to recover from Shin Splints

There are three key principles in recovery from shin splints. The principles are: de-loading of the bone, addressing the injuries causative factors, and returning to running with an appropriate loading protocol.

Let’s take a look at each:

-

Deloading the bone

Because the shin bone is overloaded the runner wishing to make a return to pain free running needs to quickly ‘get off their legs’. From personal and professional experience this is difficult to do for the obsessive runner.

The temptation is to continue to run, rationalising that the pain has settled by the time you do your next run, willfully hoping that the shin bone will not be sore after the next run. This inability to rest fully and the continued ‘shin bone dance’ of loading the bone up, making it sore, will only serve to advance a runner along the continuum towards a worsened stress reaction, and potential eventual stress fracture.

In order to avoid the advancement of the condition I recommend a minimum initial 2 weeks off normal running training. At this point I coach the injured runner that they can cross train (ride, swim, elliptical, AlterG anti-gravity treadmill) but they cannot go for even a small ‘tester’ run. I also coach the injured runner that after the initial two weeks of de-loading the shin bone, we will hop test (click HERE>>) and palpate the shin bone. At which point we are looking for no tenderness (at all) on palpating (applying gentle-moderate pressure) to the shin bone, and no pain on up to 20 single leg hops.

Typically the runner requires a second two weeks off, and in many cases up to a third two weeks off (total of 6 weeks off running). The hop test and palpation test are repeated at the end of 4 weeks, and then again if needed at the end of the 6 weeks. In many ways I find that the runners with a diagnosed stress fracture are more compliant with the required rest than the runners who have the early onset of some shin pain, or a stress reaction. The latter group of runners tend to find it difficult to refrain from loading the bone, only serving to prolong the required period of de-loading of the shin bone.

2. Addressing the causative factors

In my experience as a running focused physiotherapist I have observed there to be two groups of runners with shin pain who are on the required rest period (de-loading their shin bone). They are:

(a) the runners who understand that they need to uncover the reason(s) why they developed the shin pain in the first instance

(b) and those who ‘have their head in the sand’ hoping that rest alone will be all that is required to return to injury free running.

Obviously those runners who address the contributory factors have a much greater likelihood of making a ‘smoother’ and more prompt return to injury free running and normal training loads than those who don’t. Typically those that don’t address the underlying causative factors will return to running and suffer a recurrence of their shin pain.

This is obviously very frustrating for the runner, who at this point realises that a different approach is required. The typical risk factors that contribute to the onset of shin pain are:

- training errors (eg a sudden spike in training load-intensity, volume, or both, failure to schedule appropriate rest between sessions)

- an over-striding gait (whereby the foot lands out in front of the runner’s centre of mass increasing loads transmitted through the leg and shin)

- a deficit in hip strength (collapsing at the hips in loading will increase the loads that the runner’s body encounters with each stride cycle)

- a deficit in local calf/soleous muscle strength and endurance. It’s easy to overlook the fact that up to 55% of propulsion when running is generated from below the knee. Therefore if a runner has a deficit in calf/soleous muscle strength and endurance than this may result in increased loading of the shins (tibia). A simple calf and soleous endurance test can be used to determine if calf/soleous weakness and strength deficits exist. To perform this test simply see how many calf raises you can do on a single leg (pushing through the first and second toes with a straight leg while using one finger to balance on a wall) on a one-two second speed. Repeat this with a bent knee to determine soleous endurance. I like to set the target at 50 reps continuous for both calf and soleous endurance.

- To remedy calf endurance deficits commence calf raises eg 3x15reps> 3x20reps> 3x 30reps> 1x50reps. See below:

- To correct soleous endurance deficits commence bent leg raises eg 3x15reps> 3x20reps> 3x 30reps> 1x50reps. See below:

- Once the above is achieved (or almost achieved) I suggest commencing resistance training by either hanging onto dumbells, or kettlebells on the same side as the exercising leg (and balancing with the opposite hand) and commencing with 3x12reps before increasing weight and working on 4x8reps. Note reps should be good quality-slow and controlled. This can be done with both a straight leg (calf) and a bent knee (soleous).

- Furthering on from kettlebell or dumbell training would be the use of a smith rack in a gym setting. The benefit of using a smith rack is it removes the balance challenge experienced when trying to go heavier with dumbells or kettblebells allowing the runner to isolate the calf/soleous more. I suggest commencing with 3x12reps and adding load to get to 4-5 sets of 6-8reps. A good benchmark to aim for is 0.2-0.4x body weight being applied as load. An alternative to adding load is to slow the repetitions down, putting the exercising muscles under load for longer to try and achieve further strength gains. See below for smith rack soleous raises:

- inappropriate and/or often worn out running shoes.

For more detailed information on addressing these factors I recommend picking up a copy of my Amazon Running & Jogging Bestseller You CAN Run Pain Free! (available in both digital and physical print from Amazon, HERE>>).

3.Returning to running with an appropriate loading protocol

If the injured runner has had the appropriate rest (de-loaded their shin bone), and spent the off running time addressed the contributory factors of the injury onset, then they are ready to make a progressive return to impact loading of the shin with a return to running. This is the ‘art and science’ of rehabilitation.

‘No magic formula’

There are no ‘magic formulas’ for this part of the rehabilitation. It is incumbent that the physiotherapist or health practitioner communicates well with the runner, and also the runner’s coach if they have one. Often times I will advise a coach that the most streamlined way of ensuring the runner makes a successful return to injury free running will be for the runner to follow a prescribed return to run program that I set typically for weekly, and then fortnightly blocks for the first 4 weeks of return to running.

Recommencing speed-work

Sometimes a longer period of me prescribing a program is required, for example, getting the runner ready to commence speed work which may be anywhere from 6-12 weeks following the initial return to run program commencing. The time frames for my return to run programs are on a case by case basis, with considerations being given to the athlete’s goals, injury history, running volume, body condition etc. On a return to loading program it is critical that the runner perform self-checks on their shin for any tenderness to touch (just push the area), and any pain being produced on single leg hopping.

If pain returns

If pain returns I will advise the runner to de-load their shins for one week before retesting the hop test and palpation test. One of the biggest pitfalls runners returning to running make after required rest time, is being overzealous and doing ‘too much too soon’. Following the prescribed program is important if a recurrence of shin pain is to be avoided.

Acute on Chronic Workload -a useful tool

A useful tool that can ensure the training errors of increasing load too quickly are avoided can be the use of the Acute on Chronic Workload Ratio (ACWR). In short this tool allows runners and therapists to monitor both the external loads (distance run or length of running in minutes) as well as the internal loads (the intensity of the run-rated on perceived exertion by the runner). The average of one month’s loads (chronic load) is calculated, with every week’s load thereafter (acute load) being divided by the proceeding four weeks load to generate a ratio. There exists a ‘sweet spot’ with the ratio whereby loading of the runner’s body is deemed to be safe. To learn more click HERE>> Finding Your Optimal Training Load

Related:

To better understand bone injuries tune into the Expert Edition of The Physical Performance Show podcast featuring Professor Belinda Beck HERE>> Episode 82 Professor Belinda Beck: Bone Health Expert

All the best with your recovery from shin pain and your return to injury free running.

If you have any questions about recovery from shin splints please leave them below.

#runpainfree

Brad Beer (APAM)

Physiotherapist (APAM)

Author ‘You CAN Run Pain Free!’

Founder POGO Physio

-

[…] injury to afflict distance runners who were in training, behind tibial stress syndrome (shin splints), and Achilles tendinopathy. Amongst runners, the incidence* of plantar fasciitis ranged from 4.5 […]

Leave a Comment

Look at that handsome fella up on the header image 😉

Thanks for using my photo, Brad, and thanks for the great resource here and all of your articles! I have shared many of them with my athletes, / followers and reference them myself from time to time.

Hi Kyle,

That’s amazing-it’s a great shot!

Thanks for your support of the content.

Keep up the great work.

Regards Brad Beer