Lisfranc Injury – Diagnosis and Management

A relatively rare but often highly disabling midfoot injury is the Lisfranc Injury. This is a sprain of midfoot ligaments that causes disruption between one or more metatarsals and can have profound consequences if undetected or not managed appropriately.

Here we discuss what is a Lisfranc Injury, keys to diagnosis and important phases of management.

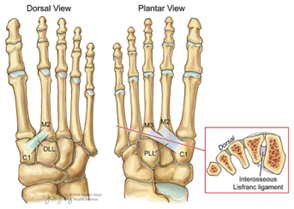

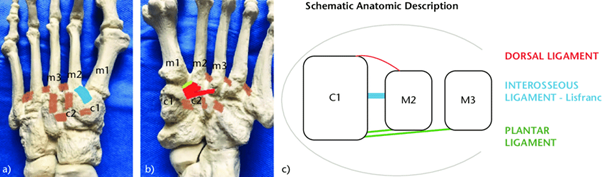

Anatomy

The Lisfranc joint is the articulation between the medial cuneiform and 2nd Metatarsal – Dorsal longitudinal ligament and plantar longitudinal ligament and interosseous lisfranc ligament. The injury can have different classification systems, it can be labelled according to how many or which metatarsals are involved. The most traumatic of which could involve an injury to all 5 metatarsals (homolateral injury). This commonly will present to emergency departments versus physiotherapy.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of subtle or incomplete Lisfranc injuries can be missed and therefore it is important to understand the mechanism of injury history. Typical mechanisms include when sporting boots (cleats or studs) get stuck into the turf with a forced plantar flexion of the forefoot, with or without rotation and the ankle moves towards dorsiflexion.

(Amirthalingam et al 2023)

It can also sound like a more typical lateral ankle sprain with plantar flexion or compression based pressures but initial location is more towards the midfoot than the lateral ankle. Other more common trauma scenarios include falling from a horse and the foot being stuck in the stirrup, falling from height or having the foot run over by a motor vehicle. A swollen midfoot and bruising under the midfoot is a typical sign. The injured person can often present with a normal x-ray but may be having trouble weight bearing. In clinic we are trying to determine if there is a functionally unstable foot as this area is built for force generation and stability.

As many are missed initially (20% may present late and undiagnosed) these may present with injuries as discussed previously, along with other signs (2). These can include difficulty to run with speed or change of direction, midfoot ‘break test’ lag when going into calf raise. One of the few clinical tests that assesses Lisfranc joint injury is the Piano Key test. This test is not tolerated well in the acute setting due to symptoms but is an important assessment of movement at each metatarsal.

Imaging

Imaging is an important feature in the assessment of Lisfranc injury. The key feature on weight bearing x-ray is separation of 1st and 2nd metatarsal, medial cuneiform gapped from 2nd metatarsal and loss of congruency from medial border 2nd metatarsal with medial border intermediate cuneiform. More subtle signs include an avulsion fragment between 1st and 2nd metatarsal bases or intermediate cuneiform. If uncertain further imaging with MRI or weight bearing CT. In 2016, a simplified Lisfranc injury classification was introduced that categorises injuries into subtle and evident types. Subtle injuries encompass Type I (Lisfranc ligament sprains with a <2 mm distance between the first and second metatarsal bases) and Type II (complete ligament rupture or ≥2 mm diastasis). Greater than 2mm appears to be a noteworthy cut out for progressing to surgical management (2,3). After combining the findings from imaging, patient history and clinical assessment a discussion can be had regarding if conservative (non-surgical) or surgical management. The vast majority will have surgery, particularly if there is fracture and instability.

Management

If surgical management is decided the patient will have an open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) involving screws and metal work to stabilise the midfoot. The metalwork is often removed at the 12 week once midfoot stiffness and healing has been achieved. Alternate surgery may include leave-in devices or fusion of the joint. It is important to note expectations; even with good quality rehabilitation, returning to the same level of sport does not occur in up to 25% of the population (5). In one study 83% players who returned and were monitored with performance and participation metrics were all down post injury. Up to 74% can have osteoarthritis changes, and 50% will develop ongoing symptomatic pain through the midfoot. Let’s outline what is involved in conservative and surgical management of these injuries.

Surgery (ORIF or fusion) and Non Surgical Management

This is intended as a guide only and will differ depending on surgeon, client, injury and a variety of individual factors. Non Surgical management will include 6 weeks non weight bearing and follow the below guide from 6 weeks onwards.

- (Post Surgery) Weeks 0-2 NWB (non-weight bearing) in a back slab cast

- Upper Limb and Contralateral Leg exercises

- Cardiovascular work NWB

- Swelling management

- Weeks 2-4 NWB in a Moonboot

- Correct Moonboot fitting often with added orthotic

- Rehab: Upper Limb and Contralateral Leg exercises

- Cardiovascular work NWB (seated ski erg, arm erg)

- Swelling management

- Non-weight bearing ankle and foot exercises

- Weeks 4-6 Touch Weight Bearing (TWB) to partial weight bearing (PWB) with surgeon permissions – potential to remain NWB to week 6

- Rehab as for weeks 2-4 with steady progressions

- Week 6-12 Heels Down Rehab

- Slow progressions from Partial to Full Weight bearing in moonboot

- Exercise in standing/sitting without rising onto toes (hence heel down) – such as heels flat leg press, front squats, leg extensions, hamstring curls, banded ankle inversion/eversion, short foot variations in standing

- No forefoot or heavy midfoot loading such as calf raises

- Single leg balance (flat surface) and stability challenges

- Ankle mobilisations to non-affected joints

- 12 Week REMOVAL OF METALWARE – at 12 weeks many who have had an ORIF will have removal of metalware and then proceed forward with the next phase

- Week 12-16 Full Weight Bearing in Normal Shoe with orthotic

- Elliptical, nordic walking or bike cardio exercise

- Strength progressions of short foot exercises such as step ups

- Calf Raises

- Lower Limb strength progressions

- Midfoot mobilisations and rearfoot mobilisations

- AlterG walking

- Dura disc balance

- Weeks 16 +

- Calf and ankle strengthening

- Progressions to plyometrics and straight line running (criteria dependent – eg > 5cm ankle range, 25+ calf raises, less than 15% difference in calf strength, painfree with brisk walking 30 min)

- Gym progressions

- Stability progressions – unstable surfaces, eyes closed, altered bases of support and multi-plane movements

- Return to training and sport 6 months – 12 months

- Return to training should be based on some specific criteria rather than time; tests such as ankle range, single leg balance (variations), no pain/swelling, single leg strength and relevant sport specific tests. This can be between 18-24 weeks post surgery or injury (5) with return to play 21-30 weeks.

- Introducing change of direction, agility and higher speed running.

Additional Considerations

Footwear and orthotics can play a large role in supporting the foot throughout the process. Input from a suitable podiatrist can be very valuable. Shoes with forefoot rockers: for example the HOKA Bondi/ASICS Glide Ride – can reduce loads of the midfoot and forefoot. In most cases if looking for maximum control of the midfoot will need custom or prefab orthoses. Additional taping for midfoot and medial ankle support can be used throughout rehabilitation particularly on return to field sessions, training and sport.

It is important to understand that an unstable Lisfranc injury is a season ending injury. It is a long 6 month plus journey and is a difficult injury to rehab effectively. An unstable foot is a non functioning foot and needs to be addressed sometimes surgically for successful rehabilitation. A well rounded rehabilitation not only focuses on the foot and ankle but also the whole person; lower limb strength and power, trunk strength and control and the cardiovascular system.

Lewis Craig (APAM)

POGO Physiotherapist

Masters of Physiotherapy

Featured in the Top 50 Physical Therapy Blog

References

- Maduka GC, Maduka DC, Yusuf N. Lisfranc Sports Injuries: What Do We Know So Far? Cureus. 2023 Nov 13;15(11):e48713. doi: 10.7759/cureus.48713. PMID: 37965234; PMCID: PMC10641664.

- Injury to the tarsometatarsal joint complex. Thompson MC, Mormino MA. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2003;11:260–267.

- Myerson MS, Fisher RT, Burgess AR, Kenzora JE. Fracture dislocations of the tarsometatarsal joints: end results correlated with pathology and treatment. Foot Ankle. 1986;6:225-242.

- Amirthalingam S, Suriyakumar S, Harshavardhan JKG. Six-Week Old Neglected Homolateral Lisfranc Injury – A Case Report. J Orthop Case Rep. 2023 May;13(5):55-59. doi: 10.13107/jocr.2023.v13.i05.3644. PMID: 37255642; PMCID: PMC10226627.

- Performance-based outcomes following Lisfranc injury among professional American football and rugby athletes. Singh SK, George A, Kadakia AR, Hsu WK. Orthopedics. 2018;41:0–82

- Stu Imer – SportsMAP Network – Physio Masterclass – Lisfranc Injury Diagnosis and Management